Upgrading vehicular access along a right of way is common in property developments. What rights does a neighbour have to object if they don’t like the upgrade to the right of way?

The NSW Court of Appeal considered this question in the decision of Owners Corporation Strata Plan 533 v Random Primer Pty Ltd [2025] NSWCA 8 (Kirk JA, Gleeson and Mitchelmore JJA agreeing) (12 February 2025).

This is an analysis.

The property development proposal

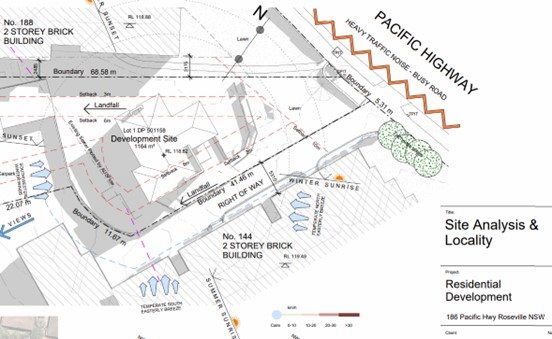

Random Primer lodged a Development Application (“DA”) to construct a new apartment building with eight dwellings and a lower ground car park for eleven cars on its land at 186 Pacific Highway, Roseville (in northern Sydney). The existing building contained two residences, with a separate carport and garage at the rear.

Strata Plan 533 is the next-door neighbour at 184 Pacific Highway, Roseville. On its land is a residential apartment building with 14 dwellings on strata title.

|

|

|

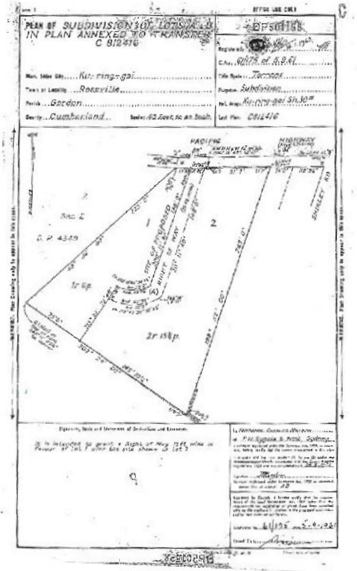

The land was subdivided into two lots in 1963. No. 184 (Lot 2) was transferred to the developer of Strata Scheme 533, subject to no. 186 (Lot 1) retaining the benefit of a right of way over the strip of land on Lot 2 that became the common driveway to provide access for car parking at the rear. The right of way was 15ft (4.572 metres) wide.

The right of way created was in the standard terms of Part 1 of Schedule 8 of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW), namely “Full and free right … for every person authorised … to go, pass and repass at all times and for all purposes with or without animals or vehicles or both to and from the dominant tenement …”.

Lot 1 had the dominant tenement with the benefit of the right of way, while Lot 2 had the servient tenement and was affected by the right of way (“ROW”).

Random Primer purchased Lot 1 in 2022 and submitted a DA. No changes to the driveway which was subject to the ROW were proposed because of the light use of the ROW. According to the transport planner, the current building on Lot 1 generates 1 vehicle trip in the morning and evening peak periods which would rise to 4.3 average trips under the proposed development.

But the Ku-ring-gai Council was not satisfied. It raised two issues: one was the “non-compliant width of the driveway”, the other was that owner’s consent had not been obtained from Strata Plan 533.

The issue of ‘non-compliant width’ was that the ROW was not wide enough to allow vehicles to pass. According to the evidence, if there was already a vehicle on the right of way when a vehicle enters in the opposite direction, the vehicle entering must reverse back down the driveway to allow the other vehicle to pass.

Random Primer lodged an amended DA to satisfy Council by increasing the width of the driveway to 6.03 metres (i.e. by adding 1.458 metres). The increase was to be inside its own land. The purpose was to create a “passing bay” to allow two vehicles to pass when entering and exiting the driveway to and from the Pacific Highway. Random Primer proposed to grant Strata Scheme 533 a right of way over this added land.

The plan of subdivision from 1963 and the amended DA site plan are reproduced at the end of this article.

Legal principles relating to the right of way

The Court stated the legal principles relating to the respective rights of the parties to be:

“The owner of the dominant tenement benefited by an easement may obtain relief from a court to protect its ability to exercise a right of way where the actions of the owner of the servient tenement constitute a substantial interference with that right.

Whether or not there has been a substantial interference involves a practical, evaluative judgment about neighbours being able to exercise their respective property rights” (at [28]-[29])

The Court identified the ‘ultimate issue’ in this case to be:

“whether the refusal of the owner of the servient tenement to give consent to the making of a development application constitutes a substantial interference in the rights held by the owner of the dominant tenement. The issue can also be expressed in converse terms of whether the servient owner’s refusal of consent was a reasonable exercise of its property rights. If it was [reasonable] then there would be no substantial interference in the rights of the dominant owner.” (at [39])

Application of the legal principles

A Court may take into account a number of considerations.

In this case, the main reason Strata Plan 533 gave to not consent to the DA was that the extension of the width of ROW was a substantial interference in its rights because it would mean that the occupants on its land would no longer be able to exit driving only on their land.

The Court took the practical view that the widening of the ROW was a Council requirement which was reasonable because it allowed people to come out and in of both sides of the land “more easily and more safely”. The Court said that only detriment to Strata Plan 533 was that drivers will be required to cross slightly over into Lot 1 when exiting. On the other hand, the refusal to consent to the DA “substantially interferes with the ability of [Random Primer] to exercise the rights granted by the easement”.

The Court upheld the trial court’s decision to grant a mandatory injunction requiring Strata Plan 533 to give its consent to the DA.

Strata Plan 533 did not pursue the common objection in these situations that the increase in vehicle trips generated by the development constituted excessive user or a substantial interference of its rights as owner of the servient tenement in the ROW. No reason was given, but it appears that the increase in width was sufficient to neutralise that objection.

Does giving consent to the DA alter rights under a right of way?

Does giving consent to a property development remove the ability to complain about the upgrade of the right of way? Or are they completely separate issues, one being a planning issue, the other a private law property issue?

The Court said:

“the private law property rights of the dominant and servient owners are distinct from the public statutory planning regime, although those areas of law intersect with respect to the giving of owner’s consent.” (at [62])

“to require the servient owner to provide consent to the making of the development application does not mean that the servient owner cannot later complain about unreasonable use by the dominant owner of the rights of way.” (at [65])

For Strata Plan 533 “to refuse its consent … was a substantial interference in the rights of [Random Primer]” (at [69])

Conclusion

If the dominant tenement owner desires to upgrade a right of way as part of a development application, the servient tenement owner should consent to the development application and raise any objections to the upgrade separately with the dominant tenement owner.

If the dominant tenement owner desires to improve the right of way, such as to change the level or surfacing or borders of the right of way, they can do so without consent so long as they do not cause substantial interference with the rights of the servient tenement owner.

|

|